Ornamental Plaster: The Modern Craftspeople Keeping an Ancient Art Alive

Plaster Demo at AHC Open House August 13, 11am-2pm

Image Caption: Apprentice Joshua Jenkins with cast and painted piece

Come see the process of restoring plaster for yourself at AHC’s upcoming Open House on August 13. The event runs from 11-2 and will feature walking tours every half hour, ice cream and live music; demonstrations by members of the Plasterers Union Local 82 begin at noon.

Kent Sickles, Business Manager of the Local 82 Plasterers Union, constantly hears the question, “Are there still people around who can restore historic ornamental plaster?” The answer is absolutely, but he’s seen buildings needlessly torn down or ornate ceilings covered over because people didn’t know that skilled plasterers exist. Not only are talented craftspeople trained in this art, but a whole new generation is learning the techniques through the Plasterers Union’s 4-year apprenticeship program.

Apprentice Program

Like the European guilds of old, apprentices train with skilled masters with years of experience on the job. Apprentices work on topics such as fireproofing, exterior stucco, patching plaster over lath and plaster walls, and ornamental plaster. The 20 to 25 apprentices come to the program from diverse backgrounds and for different reasons. The apprenticeship program is free to participants so that they are not burdened by student loans. Union members pay into a fund that covers the cost of the program. Apprentices are paid 60-90 percent of a journeyman’s rate based upon the number of class and working hours they’ve accrued. Contractors are required to use a certain number of apprentices on their jobs so the apprentices gain work experience in the field.

Tools of the trade

Ornamental plaster is cast in molds. “There are catalogs of molds that have been around for 200 years,” noted instructor Pat Roshak. He said stories exist of stealth mold makers who would sneak out at night and make castings of ornamentation on buildings to use for molds. Apprentice Jarred West emphasized the skill involved in creating ornamental plaster, “You would think that the more artistic you are, the better you’d be, but that isn’t the case because it all comes down to knowing how to use the tools.”

The basic tools of the plasterer’s trade include a trowel and a hawk. Trowel sizes are typically 12-14 inches; Kent knows some plasterers who’ve used a 16 inch trowel, but he says they’ve ended up with rotator cuff surgery. Some say the flat, square hawk was named after a falconer’s hawk because the plasterer holds it on his arm like a bird.

Ancient Art/Modern Practice

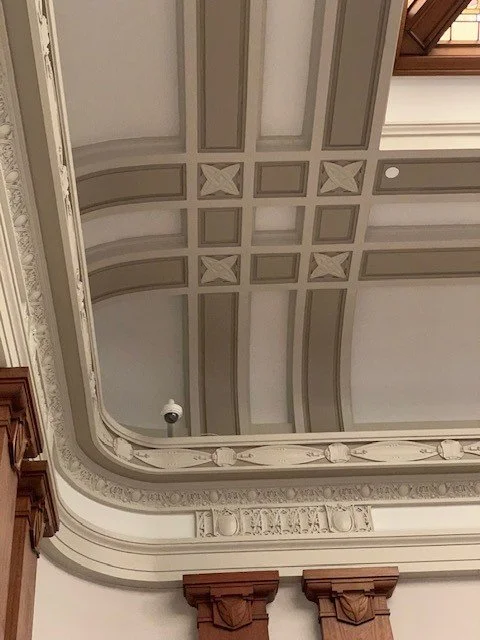

Image Caption: Oregon Supreme Court. Photo by Lainie Ettinger.

Plaster was first used as a building material in the ancient Middle East. It was mortar between blocks of the pyramids, idealized decorative relief in Greek temples, and political iconography in the form of buildings throughout the Roman Empire. Its power impressed the founders of this country who employed it in the classical architecture of Washington D.C. and the libraries, banks, schools, and courthouses of every state in the nation. Middle and upper class homeowners in the 19th and 20th centuries also swooned for plaster’s versatility. Reserved and muscular in an Arts and Crafts home, it could swirl like a wedding cake with decorative cornices, medallions, and moldings in a Second Empire mansion.

After 100 years or more, however, these homes and buildings often need repair, and members of the Plasterers Union Local 82 work on projects throughout Portland to restore and create ornamental plaster as well as more routine plaster ceiling and wall work. They’ve worked on Portland landmark buildings such as the Multnomah County Central Library, The Arlene Schnitzer Concert Hall, and area high schools (Franklin, Madison, and Grant with Benson set to begin). At the Pittock Mansion, some of the plaster work is made to look like millwork or granite.

Showcase Project: The Oregon Supreme Court

Twenty-six members of the plasterers union just completed work on one of the most complicated projects in this state in a generation–The Oregon Supreme Court building in Salem. They restored and replaced important historic ornamental plasterwork that might otherwise have been lost. Kent Sickles said, “I’ve been in the business over 40 years and this is the most ornate…intense job I’ve seen; It was big.”

Image Caption: Oregon State Supreme Court plaster motif. Photo by Lainie Ettinger.

The state was conducting a major seismic upgrade of the century-old building that required taking the walls down to the studs. Built in 1914, the Beaux Arts structure was designed by William Knighton and features a courtroom with coved corners, a Povey Brothers stained glass ceiling, and a secret drawer in the bench (as in ‘approach the bench’) that each of the justices signed over the decades. But the courtroom itself only received minor repairs in a major building project that spanned three floors including the law library, judicial chambers, and arched halls. In the law library, the Greek key patterned moldings and support corbels were all new. They had to remake all of the pieces. Classical elements fill the room, from the egg and dart pattern on the columns to the Greek key motif on the carpet, cast iron railing, and plaster moldings.

Hoffman Construction and the Harver Company conducted the project with Richard Almodovar as the Estimator/Project Manager. In June of 2021, Plaster Foreman John Adams and his team began creating castings at an outside warehouse and brought them into the courthouse once the demolition was completed. They started work onsite in October. The mold-making process involved taking the architectural elements down to make molds at the warehouse or making them in place at the building for things like the rosettes where they couldn’t use a screed–a template–so they are cast in a rubber mold. For ornamental work with a continuous shape, like patterned moldings, the team built a wood form with a metal screed on it and then made the sections of molding on a table and put them all together on the walls to make a continuous line.

John says the hardest part of the job was figuring out a way to reinstall the castings and getting them “to align and look like they had always been there so that you don’t see the transition from the new to the old.” This was particularly tricky with so many rosettes of slightly different sizes and the moldings on the ceilings painted in subtly different shades which can highlight the line breaks. John noted the additional challenge of a project of this scale, “Replicating the pieces isn’t that hard when you know how to do it, it’s keeping track of so many different pieces and how many feet of each piece you need. When you are making it six months in advance, you want to make sure you have enough, but you don’t want to have too much either.”

There is very little difference in technique or process than craftsmen would have used over one hundred years ago when the court house was built. John says, “One thing that’s different is that they used to use horse hair fibers for reinforcing and now we use fiberglass. Other than that, it’s the same plasters, same tools, and same ways to secure it to the ceilings.” For the coved ceilings, the lath is a cold-rolled steel channel liner. They didn’t have screws, or they weren’t used extensively, in 1914 when the court was built, so they used horse hair to attach the plaster. They would drape the hair over the metal in a technique called ‘wadding’ and pack it with plaster. Today, they would use mesh fiberglass and screws. (Fun fact: Kent Sickles said that the strangest thing he’s ever seen used for lath was at Providence Hospital from about WWII where seaweed panels dried to about 1 ½” thick were made into 2×4 panels and covered with plaster).

The Supreme Court project provided training for many apprentices and younger plasterers who had never seen this type of work. They learned how to cast, use rubber moldings, miter, and the difference between benching and plastering in place. Apprentice Joshua Jenkins worked on the Supreme Court building for 4 months. One of the new experiences for him was working with the metal trims and metal archways in the historic building. This project gave all of the plasterers–journeymen and apprentices–excellent experience working on a sophisticated ornamental plaster project with a tremendous number of architectural details of every kind and size. “Everyone had great ideas and we all learned from each other,” said Richard Almodovar.

Home Improvement

Image Caption: Arlington Heights home with plaster ceilings. Photo by Lainie Ettinger.

These accomplished craftspeople don’t just work on large civic projects. Much of their work is with local homeowners on smaller jobs. Chris Haynes, who works for subcontractor Fred Shearer and Sons, just completed ceiling restoration on a Dutch colonial in Arlington Heights. The process took about 5-6 business days for 4 rooms. Chris noted that in such a situation, “some people would think sheetrock is easier and they’ll rip it all out and go to all the expense of taking it down because they think it’s better in the long run.” This is a loss because plaster provides sound strength and longevity. It is also more resistant to leaks because it is not water soluble, unlike drywall. But for Chris, a journeyman with 22 years of experience, the appeal of plaster isn’t just beautiful decorative work, it’s how the house feels:

“When I walk into a house that is lath and plaster, I can tell a difference immediately, just from the air quality in a house because it breathes so much better than drywall. I know whether it’s plaster or not by the way that it sounds. I want to put plaster in because I want to retain that sound of the house.”

For those of us who live in and love old houses, it’s nice to know skilled craftspeople are still around to make sure we don’t lose the look, feel, and even the sound of historic plaster.

Story by Lainie Ettinger. Lainie is a freelance writer and AHC volunteer whose work has been published in The Oregonian and the New York Times. She has also worked in school admissions, fundraising, and communications for non-profit, cultural, and educational institutions. Lainie lives in Portland.